Kevin Kavanagh

4th April 2024

EXHIBITION: Paul Nugent – Figures in Yellow Ochre Light and Other PaintingsFROM

4th April 2024—4th May 2024

LOCATION

Kevin Kavanagh Dublin, Chancery Lane, Dublin 8, Ireland

In Antoine Watteau’s nocturnal painting L’Amour au Théâtre Italien*, a close circle of costumed commedia dell’arte performers is gathered around a lantern held aloft by one of their number – Mezzetino or Brighella – to the right of the composition. Over to the left is his more subdued counterpart, a melancholy Pierrot, playing a guitar. Behind him, another stock figure, Harlequin, gazes towards an elegantly attired actress, Isabella or Columbine, by theatrical convention his love interest. A full moon, largely obscured by clouds, sheds little light, and darkness enfolds much of the composition. There’s magic in the air.

As Watteau’s only nocturne, the painting is unusual and has engendered much speculation, though it is entirely characteristic in other respects. In fact, he inaugurated its form: the fête galante, a study of a group of figures in indeterminate, park-like settings, theatrically costumed, preoccupied by love and desire. There’s usually a musician in the compositions. But, as Robert Hughes noted, Watteau tends to capture the silences in music, the pauses, the moments before or after performance.

Watteau can be too easily classed with the more frivolous, decorative flowering of Rococo painting that followed his sadly early death from TB in 1721. But even during his lifetime, many recognised his significance. The core of his achievement was to devise a painterly language, technically beautiful and gently understated, employing an iconography of theatrical artifice, that broached the essential questions of life and human relationships while, though he lived in a tumultuous era, eschewing entirely the supposedly more serious business of history painting, then the pinnacle of the academy’s genre hierarchy.

This painting, and more generally the work of Watteau, seem especially pertinent to Paul Nugent’s Figures in Yellow Ochre Light and Other Paintings, and indeed his previous work. Watteau’s embrace of the apparatus and spirit of theatre finds a counterpart in Nugent’s previous engagement with the trappings, rituals and beliefs of Catholicism. In making his drawings and paintings, Watteau relied on a close circle of friends as models. For some of his earlier work, Nugent fabricated elaborate clerical costumes of particular religious orders of nuns and priests for his friends, their photographs serving as the basis for painted black-and-white studies. These representations were then overlaid with glazes of a single colour, to the point where the underlying images were but dimly, intermittently apparent. What might be, at first glance, monochrome abstracts with a quiet intensity, turned out to harbour images of sanctity, but any intimation of transcendence was pointedly undercut, or perhaps rendered ambiguous, by the chain of artifice involved in the process.

One could read any of these painting as a metaphor, for the phenomenon of religious faith, say, or indeed faith in anything implicit but unseen. They are metaphorically rich. A cleric plays a part in the ritual, in the hierarchical order, and in the mystique of the church, as does a stock character in the conceptual framework of the commedia. But human reality, and human longing (for love, for transcendence, for meaning) always underlies the artifice. Nugent subsequently used photographs of a sanctified space and its occupants – notably including the chapel of the famous Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris – as underlying images in paintings.

His works hum with a secret energy, and allow a remarkable range of interpretive response. The writer Catherine Morris once described to me how, as she puzzled over one of his paintings in the Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, the first she’d encountered, only half sure that she could discern in it the hazy image of an alter and its accoutrements, Ardal O’Hanlon happened to come into the gallery. To her surprise, his arrival triggered an abrupt connection in her mind between the painting’s emergent imagery, both visible and yet invisible, and the transformed relationship between the Catholic church and the Irish people that had occurred with revelations of institutional abuse and other, related scandals. With the revelations, it was as if a spell had been lifted, rendering visible what had been hidden and half-known, and the irreverent comedy of Father Ted exemplified this seismic shift.

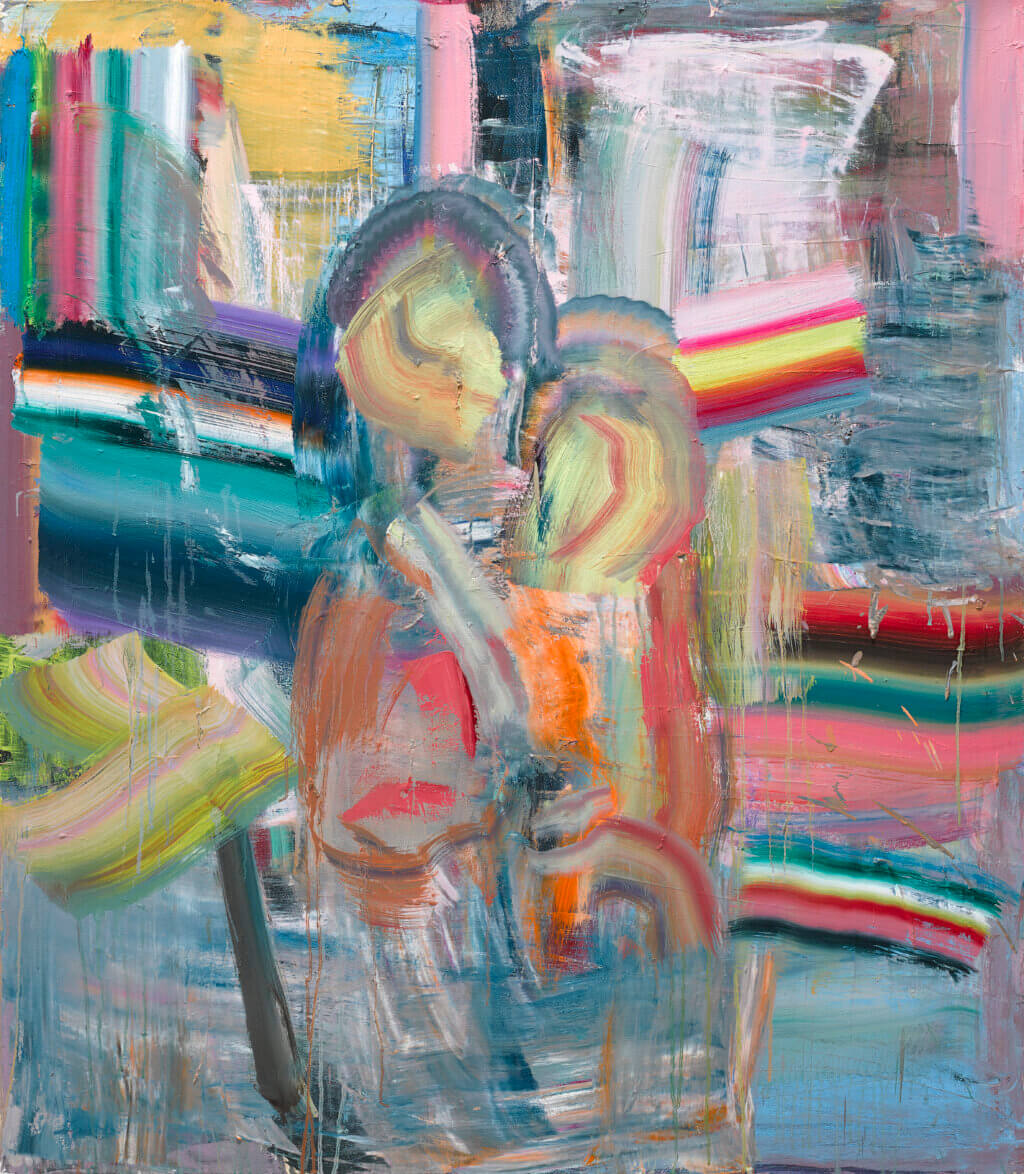

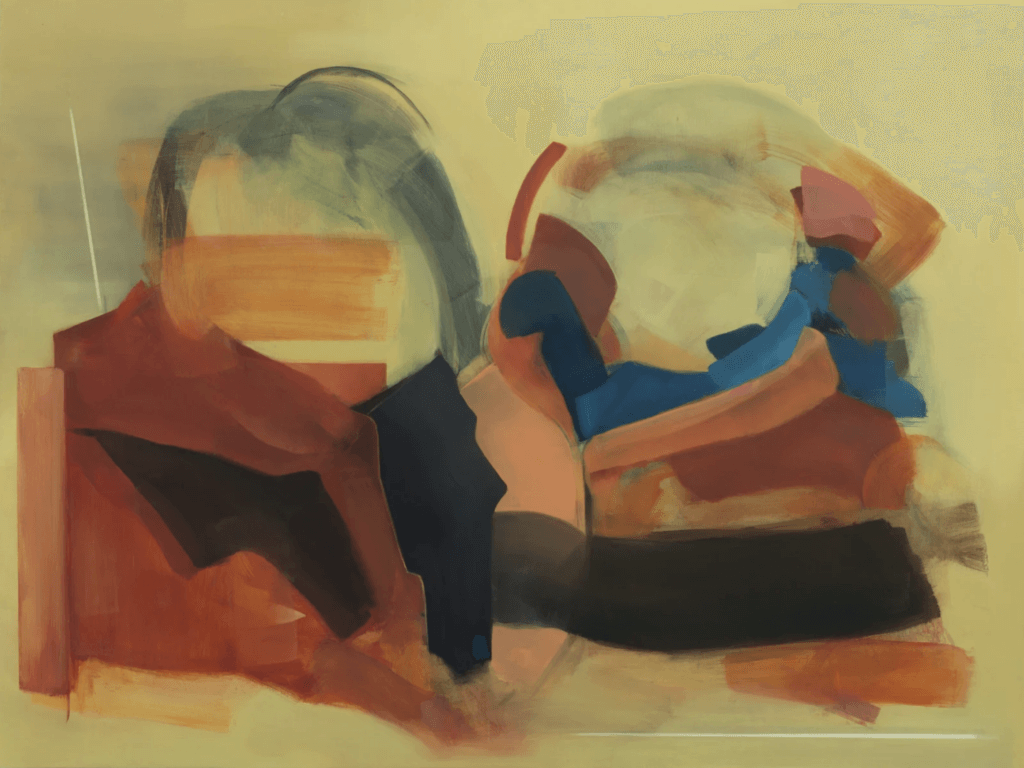

In Figures in Yellow Ochre Light, Nugent is in territory closely adjacent to Watteau’s enchanted woodlands and, again, simultaneously close to monochrome, minimalist abstraction. Each work presents a lush, inviting surface of a single colour, a surface that, on closer examination, yields evidence of a deeper layer of imagery, an inner world. The recurrent motif is, the artist notes: “The gathering of people in reverie around a central focus of smoke or illuminating fire.” It’s interesting that the illuminating fire comes with the obscuring smoke, building towards the near opacity of the dominant colour. That colour can be glowingly radiant, as with the cadmium yellow (pale) of Illumination No 1, or the flush of red (which might again be cadmium), in Gathering, or instances of yellow ochre and the palest of several blues.

Each colour is keyed to “a memory trace,” Nugent explains, a particular season and place. Within the groups of figures hazily visible, the abiding mood is calm, that of a “reverie.” There’s often a feeling of suspension, the kind of lull or pause that Hughes found in Watteau, and a comparable melancholy, tied to a sense of indeterminate but ineffable loss. Attempts to “to transcend the mundane world,” as Nugent puts it, through the promise of group endeavour and shared meaning, ritual celebration and common purpose, are evident, like hints of the sacred in previous work, but as falteringly. The two darkest and most sombre pieces are, tellingly, Ash, and Blue Monday, both of which suggest dispirited aftermaths.

These sleek paintings disclose their layers gradually and, as with Nugent’s earlier work, the closer your attention the greater the proliferation of interpretative paths that open up. Just like Watteau, while Nugent doesn’t adopt the role of the history painter, the relevance of what he does to the realities of his time is profound.

* L’Amour au Théâtre Italien, or Die italienische Komödie/The Italian Comedy, Jean Antoine Watteau (1715-1717), Berlin, Gemäldegalerie oil on canvas, 38.5X49.1cms, inv no 470

– Aidan Dunne